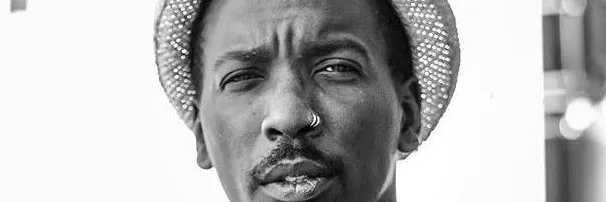

Khalil Anthony is self-identified polymath and multi-disciplinary artist. I’ve been searching for another way to describe Khalil since (tele-)meeting him, as these words seem to haunt his name on each and every platform. I’ve discovered that it’s really hard not to reuse them. Under his self-established publishing house, urban folk, inc. he has put out three albums (urbanfolksunshine, train, junebug) and five books (frederic leon, letters from the cosmos (out of print), i was drowning then i became water, and (rbn) abc affirmation coloring book volume one and volume 2.).

Khalil Anthony is self-identified polymath and multi-disciplinary artist. I’ve been searching for another way to describe Khalil since (tele-)meeting him, as these words seem to haunt his name on each and every platform. I’ve discovered that it’s really hard not to reuse them. Under his self-established publishing house, urban folk, inc. he has put out three albums (urbanfolksunshine, train, junebug) and five books (frederic leon, letters from the cosmos (out of print), i was drowning then i became water, and (rbn) abc affirmation coloring book volume one and volume 2.).

His exploration of music and literature comes together in a long list of self-produced films, which can be found here, and what’s more, Khalil also is author of a painted series titled (re)birth of a nation, in which he looks at his female ancestors. He fulfils the quota for polymath and multi-disciplinary artist.

Speaking to Khalil however, you realise that he embodies a lot more than just his work, managing to touch nearly every corner of production because he has lots to share. Despite the topic of our conversations being led by his many practices, we spoke about everything from luck and fortune to self-preservation, and from self-love to deep reciprocal friendships and community building.

In a search for how to answer the question, ‘what do you do?’, Khalil tells me that he’s been looking for a thread, for something that brings it all together. “I think I consider myself a writer. It kind of feels like in everything Im doing, writing is really important, even if its not in like the final piece” he says. From the age of 5 or 6, his mother gave him journals inspired by his love of reading, and at age 7 he was published in an international poetry journal. “I think from that moment there was this appetite for communicating outside of where I lived,” he remembers, “because I think books to me immediately avoided where I lived.” Being affirmed so early in an international space didn’t seem to him necessarily to be the fundamental roots of his success. He attributes much of the early affirmations instead to his family home, telling me, “I lived in a really amazing house with like extended family and my grandmother was the matriarch. You eat what people give you so I was thankful that I had that love from like my grandmother and my mum, these women.” With the love of these women, and then going and having accomplishments that felt big- like holding a book with his name printed inside- Khalil saw his capacities as a writer bloom at a very early age. He expresses to me that it was like “this symbiotic thing, like BOOM I want to write books.”

Though his roots will always lie in the written word, he notes how his scope beyond writing allows him the full expression of what he wants to put out into the world: “I feel like writing is a tool to get your message across and I feel like all these mediums or media are also tools to articulate my method, which I don’t feel has to be like one certain thing but I think it helps me to be grounded in whatever utensil I pick up.” Whether it’s the piano, a paintbrush, a microphone, or his feet, Khalil is committed to communicating something outside of himself, and articulating a vision. He follows, “It’s a continual process. I feel like there’s always a new opus to reach to understand myself better and I feel like these times are really intense. What do you believe in what do you stand for? Is this coming across in my work?” When I asked him how he reacts to the tension in the world today as an artist, he tells me about his beliefs in equal and opposite energies. As bad as the world can get, Khalil praises how great it can be also, and insists that “we are not islands, we are a universe. To say that the world is wrong is to say that the universe is wrong.” As an artist, to firmly look away from negative energies would seem to be a challenge; so much of art and music through time has been borne out of disruption and suffering. Khalil instead praises how awesome gravity and oxygen are, and wisely notes how “when we give something so much power to something that is sucking the energy and life force out of what we consider our day to day life it takes away from what is happening beyond our eyes.” In the midst of telling me how he doesn’t function to the best of his ability in a negative space, I realise that Khalil Anthony might have a lot more to offer me in lessons of positivity than I was prepared for.

Khalil is uniquely positive maybe something that only stuck out to me as a classic English pessimist and he’s also highly motivated. His first project to spring out of investigations into his voice happened when he was 25, living in California. Following from meeting guitarist Paris King, they brought a band together and began producing ideas and music. This led to his first album urbanfolksunshine, and as far as debut albums go, the piece was birthed in fertile grounds for music. The album was recorded entirely in analogue, at Tiny Telephone (destination for indie artists such as Death Cab for Cutie and Sleater-Kinney), and mastered at Fantasy Studios in Oakland. “These are places that are like just full of energy and so many great albums and artists have passed through those spaces” Khalil praises, “It resonates really hard for me still.” It sounds like good luck that he was able to create such a successful record in one shot, in such a creative environment. Yet despite it being a debut, he conducted himself in a way that meant he worked out a contract and pay for the musicians, so that he could fully own his work, from the off. Khalil protests the notion of a dejected creative, saying “the word artist for me was always so ubiquitous, and for me because of that I was always really anti this like ’broke artist person’ who like, has nothing to lose. It’s like no, it’s a career!” With multiple talents, and a world telling him to focus on one thing, he realised early on that he was going to have to “chart [his] own course.” He tells me, “the way I wanted to do this was you know be very professional and own my music.” He pauses, before also deconstructing the notion that this first project was entirely about luck, “At the end of the day you know I’m thankful for the opportunities I’ve had, and people say luck is the preparation meeting opportunity, you know. A lot of people are like oh you’re so lucky and I’m like yeah… and! I’m prepared and when the opportunity comes I’m like hey, oh look at this.” This ‘luck’ came into play when a few of the songs off the album appeared in a friend’s TV show, which went on to win an Emmy before the album had even come out. Despite his confidence in his work ethic, he doesn’t sit too long with the notion, for fear of it becoming “egotistical, or a little weird and above it all” and that the best way to honour where he’s gotten to is to move forwards.

Khalil remains balanced amidst it all, still. He spent the first four months of lockdown in Europe in an artist residency in Spain, where he truly learned the importance of turning off. It was a learning experience for him, he says, and that “there was a conversation with myself to experience rest, and experience maxing out on Netflix and watching whole series.” Perhaps something we all need to learn in the drive for making rent and paying bills is how there are also times when we just sit. For Khalil, it was being in nature in Spain that helped him shut off, he says “being in nature and spending that much time there, I was like ‘I can work, and when I don’t work I can actually appreciate what I’m seeing.” Khalil suggests finding that balance, and the articulation of its importance, has come out of the way the world has changed so fast. He bares how the time he spent in Spain amidst a global pandemic, and civil unrest in America was far more important to him than getting “caught up in the stuff that’s going on”. He explained to me an accusation made by a friend of his in the midst of his stay, suggesting that he was ‘hiding’ in the mountains, that he was ‘avoiding’. Yet, rather than bow under pressure to feel responsible, Khalil explains how he used his time in the mountains “close to the stars”, to address the fear of being seen as avoidant, and to embrace it. He used Spain not only to address work concerns, but personal ones, questioning, “does my body have to be on the front line of some war that I didn’t create? Is that what part of my life is about?”. He still puts a lot of importance on his place in the bigger picture, but articulates how whilst “there are some real issues that we are experiencing… if I go through those issues feeling hopeless then I don’t know what my contribution to the world looks like”. In preserving his right to answer “no” to questions of involvement, and in pioneering his disposition of positivity, the time he spent in lockdown seemed to rebalance and re-centre him.

I started to ask Khalil more of his music and the process following his first album, wondering whether he has always had a capacity for wise introspection, wondering how he transferred his energy from a live-band studio debut, to a more condensed house and electronic body of work. He began to talk about the touring band drifting apart (an all too common change of pace for musicians), but then slips into an accidental celebration of his friend Malik Crumpler. Following a quick search, I found that Crumpler is, like Khalil, a multi-disciplinary artist. A poet, rapper, producer, and editor with a large back-body of work, it seemed that two like-personas had found each other in their meeting. In touching words, Khalil gushes, “I’m so inspired by him… when you think of the word polymath, it’s more of an ambition of mine, but Malik is to me.. he’s read every book ever”. He also tells me how walking round the Louvre with Crumpler is akin to having a professional art historian to hand. One can only imagine what it’s like spending time with the two of them. The bond Khalil shares with Malik Crumpler seems truly special. His album train was the first produced after his debut, and it was created in collaboration with Crumpler. They share a compatible process and a love of Prince, and ended up recording the album in Malik’s home in two days a big jump from the refined debut. On their process, Khalil explains how, “he would play a song, I would hear it, and for me as a writer, when I hear the music and words come, I know that’s gonna be a good song… and that’s exactly what happened with us”. The album for him seemed to be a kind of breakaway from the idea of a polished “overaccomplisher”, to something more personal, or as Khalil puts it, “very much… right now”. They worked together on his most recent LP, junebug, and despite Malik being busy currently Khalil is sure about their collaboration in the future: “the way it’s always worked is it happens when it’s supposed to.”

In our conversations we talked a lot about the future, and his next five, ten, fifteen years. In five, he plans to own land and spaces where he can host artists and people, in a way that he was fortunate enough to experience in Spain this summer. “I think theres a need for spaces that accommodate the idea of what, what these artists really mean for the world.” He says, talking about the shift that’s come alongside the pandemic, wondering, “how can we make some something sustainable for artists?” with the current mass consumption of art in forms of TV, music, solitary activities. In ten years, he talks about dreams to bring a screenplay to life, based off his book Frederic Leon. Expanding his reach, he also plans on developing a production company, working around telling stories. “I think stories are, you know, for me one of the most important aspects of being alive, right, being able to tell your story, right? Hear it, read it, understand or not understand, you know, like these, real cool spaces and times where you arent focused just on yourself. Compassion can be born from that.”, he says warmly, reckoning with his love of escaping via novel, the love that set him on his artistic journey. He also hopes for a commune, an expansion on the residency spaces that could mimic a familial place, “this idea of collective lifestyle and living together and farming and growing your own food and detaching from this huge kind of like, drone ish way of being”. He doesn’t have many ideas about his fifteen-year self, but in passing words he says he wants to relearn the guitar to reconnect with his urbanfolksunshine body of work. With his productive capacity, I’m sure that will fulfil itself within the next five.

Parting ways via telephone, I ask Khalil for some advice, for young artists, or anyone willing to listen. “Take a look at who you roll with. You spend 24 hours a day with yourself…” he says off the bat. “Religion often says look to this person as your saviour, and just those few words are so messed up, ‘don’t look to yourself, look to this man who doesn’t look like you, and it’s always about him and not you’…I’ve always thought that was such a trap, don’t look at yourself, look away.” He speaks with power and intent at this moment, and continues, “When I start looking at myself I realise that I embody a saviour, a deity, I embody all of the things that you told me I needed something else to save me, like I have the capacity to be the light that I’m looking for. Like literally if you’re going in search of something, stop moving. Check in with yourself” He then pauses and says, “that’s the only advice I’d give. And that I think love and power is so important to the universe”. These were essentially the final words me and Khalil shared before life took over and we no longer spoke on the phone. He shared a lot with me in our brief interactions, and continues to share a lot with the world in his way. It makes sense that he has so many outlets, because he has a lot to say, and a lot to give.Khalil Anthony’s latest releases are June Bug from 2018, and following that SCARAB, the remix album. They are available on all major streaming platforms. You can find a catalogue of his work on his website, and follow him on Instagram, Twitter or Facebook for new projects.

Written by Mina Eyre

← Back to blog